AHGP Transcription Project

|

Boone County

Boone County, the 30th in order of formation, was organized in 1798, out of part of Campbell County; so named in honor of Col. Daniel Boone; is situated in the most northern part of the state, in the "North Bend" of the Ohio River; average length, north to south, about 20 miles, average breadth about 14 miles; bounded on the east by Kenton, south by Grant and Gallatin counties, n. and west by the Ohio River, which flows along its border about 40 miles, dividing it from the states of Ohio and Indiana. The land is nearly all tillable, a portion level, but generally hilly; the river bottoms very productive; farther out from the river, good second-rate. The principal streams are Woolper, Middle, Gunpowder, Big Bone, and Mud Lick creeks.

Members of the Legislature from Boone County, since 1859

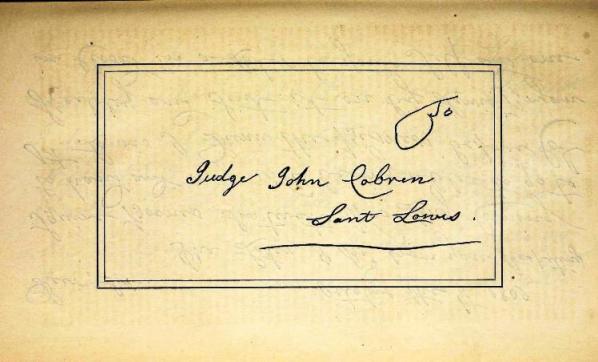

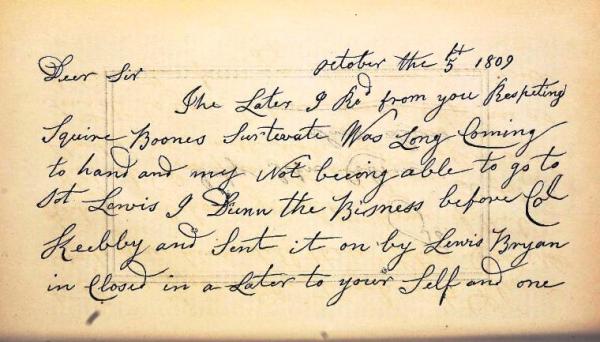

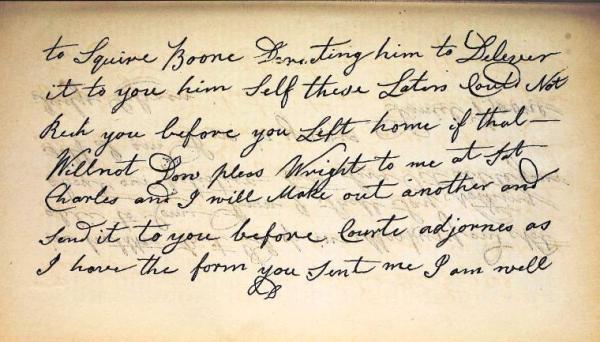

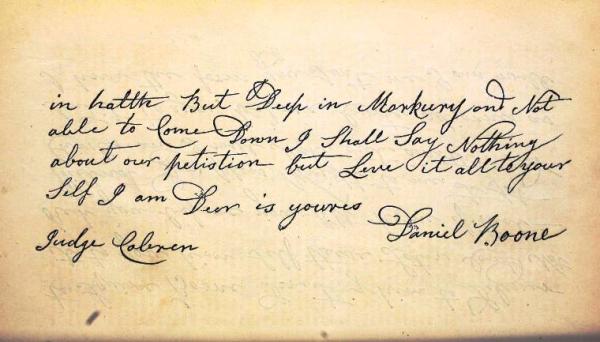

Senate  Col. Daniel Boone, who was the first white man who ever made a permanent settlement within the limits of the present State of Kentucky, was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, on the right bank of the Delaware River, on the 11th of February, 1731. Of his life, but little is known previous to his emigration to Kentucky, with the early history of which his name is, perhaps, more closely identified than that of any other man. The only sources to which we can resort for information, is the meagre narrative dictated by himself, in his old age, and which is confined principally to that period of his existence passed in exploring the wilderness of Kentucky, and which, therefore, embraces but a comparatively small part of his life; and the desultory reminiscences of his early associates in that hazardous enterprise. This constitutes the sum total of our knowledge of the personal history of this remarkable man, to whom, as the founder of what may without impropriety be called a new empire, Greece and Rome would have erected statues of honor, if not temples of worship. It is said that the ancestors of Daniel Boone were among the original Catholic settlers of Maryland; but of this nothing is known with certainty, nor is it, perhaps, important that anything should be. He was eminently the architect of his own fortunes; a self-formed man in the truest sense, whose own innate energies and impulses, gave the molding impress to his character. In the years of his early boyhood, his father immigrated first to Reading, on the head waters of the Schuylkill, and subsequently to one of the valleys of south Yadkin, in North Carolina, where the subject of this notice continued to reside until his fortieth year. Our knowledge of his history during this long interval, is almost a perfect blank; and although we can well imagine that he could not have passed to this mature age, without developing many of those remarkable traits, by which his subsequent career was distinguished, we are in possession of no facts out of which to construct a biography of this period of his life. We know, indeed, that from his earliest years he was distinguished by a remarkable fondness for the exciting pleasures of the chase; that he took a boundless delight in the unrestrained freedom, the wild grandeur and thrilling solitude of those vast primeval forests, where nature in her solemn majesty, unmarred by the improving hand of man, speaks to the impressionable and unhacknied heart of the simple woodsman, in a language unknown to the dweller in the crowded haunts of men. But, in this knowledge of his disposition and tastes, is comprised almost all that can absolutely be said to be known of Daniel Boone, from his childhood to his fortieth year. In 1767, the return of Findlay from his adventurous excursion into the unexplored wilds beyond the Cumberland mountain, and the glowing accounts he gave of the richness and fertility of the new country, excited powerfully the curiosity and imaginations of the frontier backwoodsmen of Virginia and North Carolina, ever on the watch for adventures; and to whom the lonely wilderness, with all its perils, presented attractions which were not to be found in the close confinement and enervating inactivity of the settlements. To a man of Boone's temperament and tastes, the scenes described by Findlay, presented charms not to be resisted; and, in 1769, he left his family upon the Yadkin, and in company with five others, of whom Findlay was one, he started to explore that country of which he had heard so favorable an account. Having reached a stream of water on the borders of the present State of Kentucky, called Red River, they built a cabin to shelter them from the inclemency of the weather, (for the season had been very rainy), and devoted their time to hunting and the chase, killing immense quantities of game. Nothing of particular interest occurred until the 22nd December, 1769, when Boone, in company with a man named Stuart, being out hunting, they were surprised and captured by Indians. They remained with their captors seven days, until having by a rare and powerful exertion of self-control, suffering no signs of impatience to escape them, succeeded in disarming the suspicions of the Indians, their escape was effected without difficulty. Through life, Boone was remarkable for cool, collected self-possession, in moments of most trying emergency, and on no occasion was this rare and valuable quality more conspicuously displayed than during the time of this captivity. On regaining their camp, they found it dismantled and deserted. The fate of its inmates was never ascertained, and it is worthy of remark, that this is the last and almost the only glimpse we have of Findlay, the first pioneer. A few days after this, they were joined by Squire Boone, a brother of the great pioneer, and another man, who had followed them from Carolina, and accidentally stumbled on their camp. Soon after this accession to their numbers, Daniel Boone and Stuart, in a second excursion, were again assailed by the Indians, and Stuart shot and scalped; Boone fortunately escaped. Their only remaining companion, disheartened by the perils to which they were continually exposed, returned to North Carolina; and the two brothers were left alone in the wilderness, separated by hundreds of miles from the white settlements, and destitute of everything but their rifles. Their ammunition running short, it was determined that Squire Boone should return to Carolina for a fresh supply, while his brother remained in charge of the camp. This resolution was accordingly carried into effect, and Boone was left for a considerable time to encounter or evade the teeming perils of his hazardous solitude alone. We should suppose that his situation now would have been disheartening and wretched in the extreme. He himself says, that for a few days after his brother left him, he felt dejected and lonesome, but in a short time his spirits recovered their wonted equanimity, and he roved through the woods in every direction, killing abundance of game and finding an unutterable pleasure in the contemplation of the natural beauties of the forest scenery. On the 27th of July, 1770, the younger Boone returned from Carolina with the ammunition, and with a hardihood almost incredible, the brothers continued to range through the country without injury until March, 1771, when they retraced their steps to North Carolina. Boone had been absent from his family for near three years, during nearly the whole of which time he had never tasted bread or salt, nor beheld the face of a single white man, with the exception of his brother and the friends who had been killed. We, of the present day, accustomed to the luxuries and conveniences of a highly civilized state of society—lapped in the soft indolence of a fearless security, accustomed to shiver at every blast of the winter's wind, and to tremble at every noise the origin of which is not perfectly understood, can form but an imperfect idea of the motives and influences which could induce the early pioneers of the west to forsake the safe and peaceful settlements of their native States, and brave the unknown perils, and undergo the dreadful privations of a savage and un-reclaimed wilderness. But, in those hardy hunters, with nerves of iron and sinews of steel, accustomed from their earliest boyhood to entire self-dependence for the supply of every want, there was generated a contempt of danger and a love for the wild excitement of an adventurous life, which silenced all the suggestions of timidity or prudence. It was not merely a disregard of danger which distinguished these men, but an actual insensibility to those terrors which palsy the nerves of men reared in the peaceful occupations of a densely populated country. So deep was this love of adventure, which we attribute as the distinguishing characteristic of the early western hunters, implanted m the breast of Boone, that he determined to sell his farm, and remove with his family to Kentucky. Accordingly, on the 25th of September, 1773, having disposed of all his property, except that which he intended to carry with him to his new home, Boone and his family took leave of their friends, and commenced their journey west. In Powell's valley, being joined by five more families and forty men, well-armed, they proceeded towards their destination with confidence; but when near the Cumberland Mountains, they were attacked by a large party of Indians. These, after a severe engagement, were beaten off and compelled to retreat; not, however, until the whites had sustained a loss of six men in killed and wounded. Among the killed, was Boone's eldest son. This foretaste of the dangers which awaited them in the wilderness they were about to explore, so discouraged the emigrants, that they immediately retreated to the settlements on Clinch River, a distance of forty miles from the scene of action. Here they remained until 1775. During this interval, Boone was employed by Governor Dunmore, of Virginia, to conduct a party of surveyors through the wilderness, from Falls of the Ohio, a distance of eight hundred miles. Of the incidents attending this expedition, we have no account whatever. After his return, he was placed by Dunmore in command of three frontier stations, or garrisons, and engaged in several affairs with the Indians. At about the same period, he also, at the solicitation of several gentlemen of North Carolina, attended a treaty with the Cherokees, known as the treaty of Wataga, for the purchase of the lands south of the Kentucky River. It was in connection with this land purchase, and under the auspices of Col. Richard Henderson, that Boone's second expedition to Kentucky was made. His business was to mark out a road for the pack-horses and wagons of Henderson's party. Leaving his family on Clinch River, he set out upon this hazardous undertaking at the head of a few men, on the 10th of March, 1775, and arrived, without any adventure worthy of note, on the 25th of March, the same year, at a point within fifteen miles of the spot where Boonesborough was afterwards built. Here they were attacked by Indians, and it was not until after a severe contest, and loss on the part of the whites of three men in killed and wounded, that they were repulsed. An attack was made on another party, and the whites sustained a loss of two more. On the 1st of April, they reached the southern bank of the Kentucky River, and began to build a fort, afterwards known as Boonesborough. On the 4th, they were again attacked by the Indians, and lost another man; but, notwithstanding the dangers to which they were continually exposed, the work was prosecuted with indefatigable diligence, and on the 14th of the month finally completed. Boone shortly returned to Clinch River for his family, determined to remove them to this new and remote settlement at all hazards. This was accordingly effected as soon as circumstances would permit. From this time, the little garrison was exposed to incessant assaults from the Indians, who appeared to be perfectly infuriated at the encroachments of the whites, and the formation of settlements in the midst of their old hunting grounds; and the lives of the emigrants were passed in a continued succession of the most appalling perils, which nothing but unquailing courage and indomitable firmness could have enabled them to encounter. They did, however, breast this awful tempest of war, and bravely and successfully, and in defiance of all probability, the small colony continued steadily to increase and flourish, until the thunder of barbarian hostilities rolled gradually away to the north, and finally died in low mutterings on the frontiers of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. The summary nature of this sketch will not admit of more than a bare enumeration of the principal events in which Boone figured, in these exciting times, during which he stood the center figure, towering like a colossus amid that hardy band of pioneers, who exposed their breasts to the shock of that dreadful death struggle, which gave a yet more terrible significance, and a still more crimson hue, to the history of the old dark and bloody ground. In July, 1776, the people at the Fort were thrown into the greatest agitation and alarm, by an incident characteristic of the times, and which singularly illustrates the habitual peril which environed the inhabitants. Jemima Boone and two daughters of Col. Callaway were amusing themselves in the neighborhood of the fort, when a party of Indians suddenly rushed from the surrounding coverts and carried them away captives. The screams of the terrified girls aroused the inmates of the garrison: but the men being generally dispersed in their usual avocations, Boone hastily pursued with a party of only eight men. The little party, alter marching hard during two nights, came up with the Indians early the third day, the pursuit having been conducted with such silence and celerity that the savages were taken entirely by surprise, and having no preparations for defense, they were routed almost instantly, and without difficulty. The young girls were restored to their gratified parents without having sustained the slightest injury, or any inconvenience beyond the fatigue of the march and a dreadful fright. The Indians lost two men, while Boone's party was uninjured. From this time until the 15th of April, the garrison was constantly harassed by flying parties of savages. They were kept in continual anxiety and alarm; and the most ordinary duties could only be performed at the risk of their lives. "While plowing their corn, they were way-laid and shot; while hunting, they were pursued and fired upon; and sometimes a solitary Indian would creep up near the fort during the night, and fire upon the first of the garrison who appeared in the morning." On the 15th of April, a large body of Indians invested the fort, hoping to crush the settlement at a single blow; but, destitute as they were of scaling ladders, and all the proper means of reducing fortified places, they could only annoy the garrison, and destroy the property; and being more exposed than the whites, soon retired precipitately. On the 4th of July following, they again appeared with a force of two hundred warriors, and were repulsed with loss. A short period of tranquility was now allowed to the harassed and distressed garrison; but this was soon followed by the most severe calamity that had yet befallen the infant settlement. This was the capture of Boone and twenty-seven of his men in the month of January 1778, at the Blue Licks, whither he had gone to make salt for the garrison. He was carried to the old town of Chillicothe, in the present state of Ohio, where he remained a prisoner with the Indians until the 16th of the following June, when he contrived to make his escape, and returned to Boonesborough. During this period, Boone kept no journal, and we are therefore uninformed as to any of the particular incidents which occurred during his captivity. We only know, generally, that, by his equanimity, his patience, his seeming cheerful submission to the fortune which had made him a captive, and his remarkable skill and expertness as a woodsman, he succeeded in powerfully exciting the admiration and conciliating the good will of his captors. In March, 1778, he accompanied the Indians on a visit to Detroit, where Governor Hamilton offered one hundred pounds for his ransom, but so strong was the affection of the Indians for their prisoner, that it was unhesitatingly refused. Several English gentlemen, touched with sympathy for his misfortunes, made pressing offers of money and other articles, but Boone steadily refused to receive benefits which he could never return. On his return from Detroit, he observed that large numbers of warriors had assembled, painted and equipped for an expedition against Boonesborough, and his anxiety became so great that he determined to affect his escape at every hazard. During the whole of this agitating period, however, he permitted no symptom of anxiety to escape; but continued to hunt and shoot with the Indians as usual, until the morning of the 16th of June, when, making an early start, he left Chillicothe, and shaped his course for Boonesborough. This journey, exceeding a distance of one hundred and fifty miles, he performed in four days, during which he ate only one meal. He was received at the garrison like one risen from the dead. His family supposing him killed, had returned to North Carolina; and his men, apprehending no danger, had permitted the defenses of the fort to fall to decay. The danger was imminent; the enemy were hourly expected, and the fort was in no condition to receive them. Not a moment was to be lost: the garrison worked night and day, and by indefatigable diligence, everything was made ready within ten days after his arrival, for the approach of the enemy. At this time one of his companions arrived from Chillicothe, and reported that his escape had determined the Indians to delay the invasion for three weeks. The attack was delayed so long that Boone, in his turn, resolved to invade the Indian country; and accordingly, at the head of a select company of nineteen men, he marched against the town of Paint Creek, on the Scioto, within four miles of which point he arrived without discovery. Here he encountered a party of thirty warriors, on their march to join the grand army in its expedition against Boonesborough. This party he attacked and routed without loss or injury to himself; and, ascertaining that the main body of the Indians were on their march to Boonesborough, he retraced his steps for that place with all possible expedition. He passed the Indians on the 6th day of their march, and on the 7th reached the fort. The next day the Indians appeared in great force, conducted by Canadian officers well skilled in all the arts of modern warfare. The British colors were displayed and the fort summoned to surrender. Boone requested two days for consideration, which was granted. At the expiration of this period, having gathered in their cattle and horses, and made every preparation for a vigorous resistance, an answer was returned that the fort would be defended to the last. A proposition was then made to treat, and Boone and eight of the garrison, met the British and Indian officers, on the plain in front of the fort. Here, after they had gone through the farce of pretending to treat, an effort was made to detain the Kentuckians as prisoners. This was frustrated by the vigilance and activity of the intended victims, who springing out from the midst of their savage foemen, ran to the fort under a heavy fire of rifles, which fortunately wounded only one man. The attack instantly commenced by a heavy fire against the picketing, and was returned with fatal accuracy by the garrison. The Indians then attempted to push a mine into the fort, but their object being discovered by the quantity of fresh earth they were compelled to throw into the River, Boone cut a trench within the fort, in such a manner as to intersect their line of approach, and thus frustrated their design. After exhausting all the ordinary artifices of Indian warfare, and finding their numbers daily thinned by the deliberate and fatal fire from the garrison, they raised the siege on the ninth day after their first appearance, and returned home. The loss on the part of the garrison, was two men killed and four wounded. Of the savages, twenty-seven were killed and many wounded, who, as usual, were carried off. This was the last siege sustained by Boonesborough. In the fall of this year, Boone went to North Carolina for his wife and family, who, as already observed, had supposed him dead, and returned to their kindred. In the summer of 1780, he came back to Kentucky with his family, and settled at Boonesborough. In October of this year, returning in company with his brother from the Blue Licks, where they had been to make salt, they were encountered by a party of Indians, and his brother, who had been his faithful companion through many years of toil and danger, was shot and scalped before his eyes. Boone, after a long and close chase, finally effected his escape. After this, he was engaged in no affair of particular interest, so far as we are informed, until the month of August, 1782, a time rendered memorable by the celebrated and disastrous battle of the Blue Licks. A full account of this bloody and desperate conflict, will be found under the head of Nicholas County, to which we refer the reader. On this fatal day, he bore himself with distinguished gallantry, until the rout began, when, after having witnessed the death of his son, and many of his dearest friends, he found himself almost surrounded at the very commencement of the retreat. Several hundred Indians were between him and the ford, to which the great mass of the fugitives were bending their way, and to which the attention of the savages was particularly directed. Being intimately acquainted with the ground, he together with a few friends, dashed into the ravine which the Indians had occupied, but which most of them had now left to join in the pursuit. After sustaining one or two heavy fires, and baffling one or two small parties who pursued him for a short distance, he crossed the river below the ford by swimming, and returned by a circuitous route to Bryan station Boone accompanied General George Rogers Clark, in his expedition against the Indian towns, undertaken to avenge the disaster at the Blue Licks; but be yond the simple fact that he did accompany this expedition, nothing is known of his connection with it: and it does not appear that he was afterwards engaged in any public expedition or solitary adventure. The definitive treaty of peace between the United States and Great Britain, in 1783, confirmed the title of the former to independence, and Boone saw the standard of civilization and freedom securely planted in the wilderness. Upon the establishment of the court of commissioners in 1779, he had laid out the chief of his little property to procure land warrants, and having raised about twenty thousand dollars in paper money, with which he intended to purchase them, on his way from Kentucky to the city of Richmond, he was robbed of the whole, and left destitute of the means of procuring more. Unacquainted with the niceties of the law, the few lands he was enabled afterwards to locate, were, through his ignorance, swallowed up and lost by better claims. Dissatisfied with these impediments to the acquisition of the soil, he left Kentucky, and in 1795, he was a wanderer on the banks of the Missouri, a voluntary subject of the king of Spain. The remainder of his life was devoted to the society of his children, and the employments of the chase, to the latter especially. When age had enfeebled the energies of his once athletic frame, he would wander twice a year into the remotest wilderness he could reach, employing a companion whom he bound by a written contract to take care of him, and bring him home alive or dead. In 1816, he made such an excursion to Fort Osage, one hundred miles distant from the place of his residence. "Three years thereafter," says Gov. Morehead, "a patriotic solicitude to preserve his portrait, prompted a distinguished American artist to visit him at his dwelling near the Missouri River, and from him I have received the following particulars: He found him in a small, rude cabin, indisposed, and reclining on his bed. A slice from the loin of a buck, twisted round the rammet of his rifle, within reach of him as he lay, was roasting before the fire. Several other cabins, arranged in the form of a parallelogram, marked the spot of a dilapidated station. They were occupied by the descendants of the pioneer. Here he lived in the midst of his posterity. His withered energies and locks of snow, indicated that the sources of existence were nearly exhausted." He died of fever, at the house of his son-in-law, Flanders Callaway, at Charette village, on the Missouri River, September 26, 1820, aged 89. The legislature of Missouri in sessional St. Louis, when the event was announced, resolved that, in respect for his memory, the members would wear the usual badge of mourning for twenty days, and voted an adjournment for that day. It has been generally supposed that Boone was illiterate, and could neither read nor write, but this is an error. There was, in 1846, in possession of the late Joseph B. Boyd, of Maysville, an autograph letter of the old woodsman, a facsimile of which is herewith published.     The following vigorous and eloquent portrait of the character of the old pioneer, is extracted from Gov. Morehead's address, delivered at Boonesborough, in commemoration of the first settlement of Kentucky: "The life of Daniel Boone is a forcible example of the powerful influence which a single absorbing passion exerts over the destiny of an individual. Born with no endowments of intellect to distinguish him from the crowd of ordinary men, and possessing no other acquirements than a very common education bestowed, he was enabled, nevertheless, to maintain through a long and useful career, a conspicuous rank among the most distinguished of his contemporaries; and the testimonials of the public gratitude and respect with which he was honored after his death, were such as are never awarded by an intelligent people to the undeserving. * * * * He came originally to the wilderness, not to settle and subdue it, but to gratify an inordinate passion for adventure and discovery to hunt the deer and buffalo, to roam through the woods, to admire the beauties of nature, in a word, to enjoy the lonely pastimes of a hunter's life, remote from the society of his fellow men. He had heard, with admiration and delight, Finley's description of the country of Kentucky, and high as were his expectations, he found it a second paradise. Its lofty forests—its noble rivers—its picturesque scenery its beautiful valleys, but above all, the plentyfulness of "beasts of every American kind" these were the attractions that brought him to it. * * * * * He united, in an eminent degree, the qualities of shrewdness, caution, and courage, with uncommon muscular strength. He was seldom taken by surprise, he never shrunk from danger, nor cowered beneath the pressure of exposure and fatigue. In every emergency, he was a safe guide and a wise counsellor, because his movements were conducted with the utmost circumspection, and his judgment and penetration were proverbially accurate. Powerless to originate plans on a large scale, no individual among the pioneers could execute with more efficiency and success the designs of others. He took the lead in no expedition against the savages, he disclosed no liberal and enlarged views of policy for the protection of the stations; and yet it is not assuming too much to say, that without him, in all probability, the settlements could not have been upheld, and the conquest of Kentucky might have been reserved for the emigrants of the nineteenth century. ***** His manners were simple and unobtrusive, exempt from the rudeness characteristic of the backwoodsman. In his person there was nothing remarkably striking. He was five feet ten inches in height, and of robust and powerful proportions. His countenance was mild and contemplative, indicating a frame of mind altogether different from the restlessness and activity that distinguished him. His ordinary habiliments were those of a hunter, a hunting shirt and moccasins uniformly composing a part of them. When he immigrated to Louisiana, he omitted to secure the title to a princely estate, on the Missouri, because it would have cost him the trouble of a trip to New Orleans. He would have traveled a much greater distance to indulge his cherished propensities as an adventurer and a hunter. He died, as he had lived, in a cabin, and perhaps his trusty rifle was the most valuable of his chattels. "Such was the man to whom has been assigned the principal merit of the discovery of Kentucky, and who filled a large space in the eyes of America and Europe. Resting on the solid advantages of his services to his country, his fame will survive, when the achievements of men, greatly his superiors in rank and intellect, will be forgotten." (For an account of the removal of the mortal remains of Boone and his wife from Missouri to Kentucky, and their re-interment at Frankfort, see Franklin County.) Source: History of Kentucky, Volume II, by Lewis Collins, Published by Collins & Company, Covington, Kentucky, 1874 |